They’re all the rage these days, with teams using them to free up their cash flow, players using them for long-term security and tax advantages purposes, and fans using the practice as reason to lash out at the Los Angeles Dodgers’ payroll.

Deferred contracts.

Teams love them.

Players manipulate them.

And Bobby Bonilla takes great pride in them.

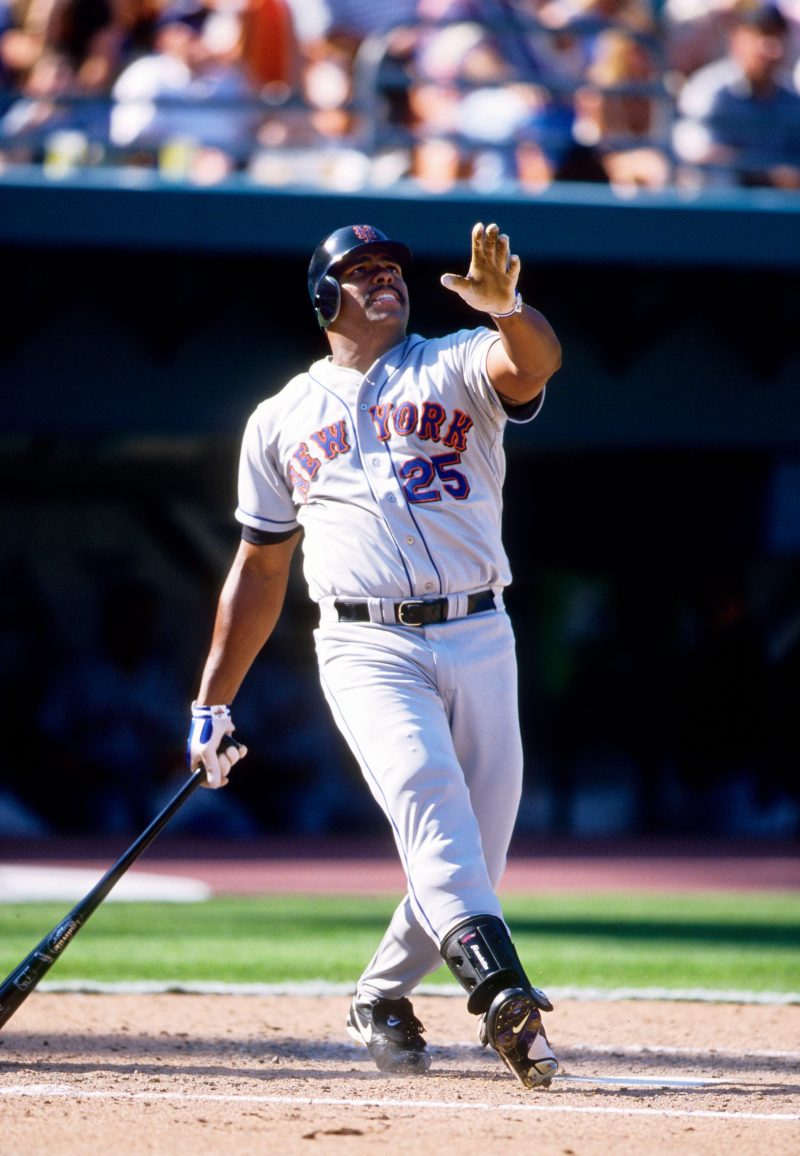

Bonilla, 62, the six-time All-Star and World Series champion who once was the game’s highest-paid player, wasn’t the first player to receive a deferred contract – but none are more famous.

He has become known as the godfather of deferrals, with Bonilla and former agent Dennis Gilbert orchestrating an ingenious deal a quarter-century ago with New York Mets that has become a trend-setter.

Everywhere you turn these days, players and teams are negotiating contracts with massive deferrals.

Shohei Ohtani took it to a new level two years ago when he signed a 10-year, $700 million contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers, deferring a stunning $68 million a year without interest. The contract is reduced to $460 million in present-day value, saving the Dodgers $24 million a year in luxury taxes. And for Ohtani, it’s a savings of about $98 million, avoiding California taxes on the $68 million annual payments if he’s no longer a California resident in 10 years.

Free agent outfielder Kyle Tucker just signed a four-year, $240 million contract with the Dodgers, which not only included $30 million in deferrals, but a $64 million signing bonus that’s payable before he leaves for spring training. It’s a brilliant move considering the signing bonus won’t be subject to California taxes, saving about $9.2 million since he’s a Florida resident with no state taxes.

Tucker’s deal was a page out of Vladimir Guerrero’s playbook a year ago when he signed a 14-year, $500 million contract with the Toronto Blue Jays. He and his agents, Barry Praver and Scott Shapiro, negotiated an MLB record $325 million signing bonus. It allows Guerrero, a Florida resident, to be taxed at 15% of the bonus as opposed to the 53.5% of Canadian wages, saving him $123.5 million.

Veteran starter Max Scherzer still is being paid $15 million annually from the Washington Nationals in his original seven-year, $210 million contract, negotiated by Scott Boras in 2015.

The king of deferrals are the Dodgers, owned by Guggenheim, who have $1.0945 billion owed in deferrals to 10 different players from 2028-2047.

Look around, and virtually every major free-agent contract this winter has included deferrals.

Tucker, Dodgers: 4 years, $240 million, $30 million deferred.

Dylan Cease, Toronto Blue Jays: 7 years, $210 million, $64 million deferred.

Alex Bregman, Chicago Cubs: 5 years, $175 million, $70 million deferred.

Edwin Diaz, Dodgers: 3 years, $69 million, $13.5 million deferred.

Devin Williams, New York Mets: 3 years, $51 million, $15 million deferred.

The clubs pay less in luxury taxes and have more disposal income to enhance their roster, while the players are able to use it to negotiate a larger contract, while lowering their personal tax burden.

“You’re seeing it everywhere now in the large contracts,’ says Robert Raiola, director of the sports and entertainment group at PKF O’Connor Davies, a CPA and business consulting firm. “The deferred money allows teams financial flexibility for current payroll and luxury tax management.

“And for the players, it’s a savings, because most states are not going to tax deferred money as long as the players are not performing services in that state when they receive that deferred money.’

Certainly, Cease’s $210 million contract is a prime example benefiting the Blue Jays and himself. His deferrals reduce his contract to $184.63 million in present-day value, lowering the Blue Jays’ AAV for competitive balance tax purposes to $26.375 million instead of $30 million. And for Cease, he’s not only spared Canada’s stiff tax rate on his deferrals, but also on his $23 million signing bonus.

While players have now embraced deferrals, there’s an enormous difference between today’s deferrals and Bonilla’s deal from 2025. Bonilla was paid 8% interest on his $5.9 million buyout, paying him $1.19 million annually for 25 years through 2035. Bonilla, with the guidance of his former agent, turned $5.9 million into nearly $30 million.

The contract now has become legendary, with July 1 now being called “Bobby Bonilla Day’’ in baseball, the day he receives his annual check.

“It’s a beautiful thing,’ Bonilla tells USA TODAY Sports. “It gets so much publicity now, it’s become bigger than my birthday.’

Bonilla, 62, who was a special assistant for the Major League Baseball Players Association, now is a spokesman for the Players Trust, a non-profit arm of the union. They will have their annual Playmakers Classic event on Feb. 18 in Phoenix, sponsored by Fanatics, with proceeds from the event going towards youth development baseball programs across the country and abroad.

“What is there not to be excited about?’’ Bonilla said. “It’s going to be an awesome interactive event, and we get to see the retired and active players, have some nice wine, smoke some cigars, and then mingle with all the sponsors and everything. It’s just beautiful.’

Certainly, at some juncture during the event, Bonilla once again will be ask about the famous contract, particularly by players who may be considering deferrals in their next contract. Bonilla says he won’t hesitate telling them it was one of the best financial decisions he ever made.

“I wasn’t afraid to put the money away,’ Bonilla said. “Everybody’s wanting their stuff now. I wanted to make sure that I had money later on. I was really, was never extravagant. I wasn’t a hermit or anything. I bought what I wanted.

“I had a couple of cars.

“But I didn’t have 12 of them.’

Bonilla and Mets owner Steve Cohen have talking about having an event every year on July 1 to celebrate the occasion, a Citi Field “Bobby Bonilla Day,’ but for now, it remains on the backburner

“Me and Steve have talked about it,’ Bonilla said, “but he’s busy trying to bring a championship to New York. Steve’s going to do everything he can to make it happen. I know how badly Mets fans want that championship, but in this game, you just have to be patient.’

Bonilla was on that ’92 Mets team that resembled last year’s edition of the Mets with their star talent, bloated payroll, and miserable failures. They had several aging stars on their 72-90 team like 36-year-old Eddie Murray, but it also included a young 24-year-old second baseman.

Bonilla never envisioned the kid would one day wind up in Cooperstown, N.Y.: Jeff Kent.

“He was a great second baseman, just a wonderful player,’ Bonilla said. “I’m so happy for him. He was certainly worthy of getting in.’

Bonilla also played with 10-time Gold Glove center fielder Andruw Jones in Atlanta, who’s also being inducted into the Hall of Fame along with former Mets center fielder Carlos Beltran.

“He was so special, so gifted,’ Bonilla said of Jones. “This is how good he was: I’m in left field one day, and the first pop-up hit to me, I lose it. Andruw sees that I lost it, yells, “Don’t worry, Bo, I got it. I mean, I gave no indication I lost the ball, but he recognized that, flies over, catches it, and laughs. He saved my butt. That’s how good he was.’’

Still, as thrilled as Bonilla is for Kent and Jones, he hopes one day another former teammate and close friend will receive baseball’s greatest honor. Yep, Barry Bonds.

“You know how I feel about Barry getting in,’ Bonilla said. “He belongs. I don’t know what the hang up is with everybody leaving Barry off. I mean, statistically no one’s even close. He was just so good. He’s the best I’ve ever seen, and it’s just crazy he’s not in there. We all scratch our head.

“So, I’m going to keep advocating for BB because I want him in there so bad.’

In the meantime, if you ever need to talk contracts, and the financial advantages of deferred money, Bobby Bo is your man.

Sure, he won’t make the Hall of Fame, but that contract sure might.

Follow Nightengale on X: @Bnightengale