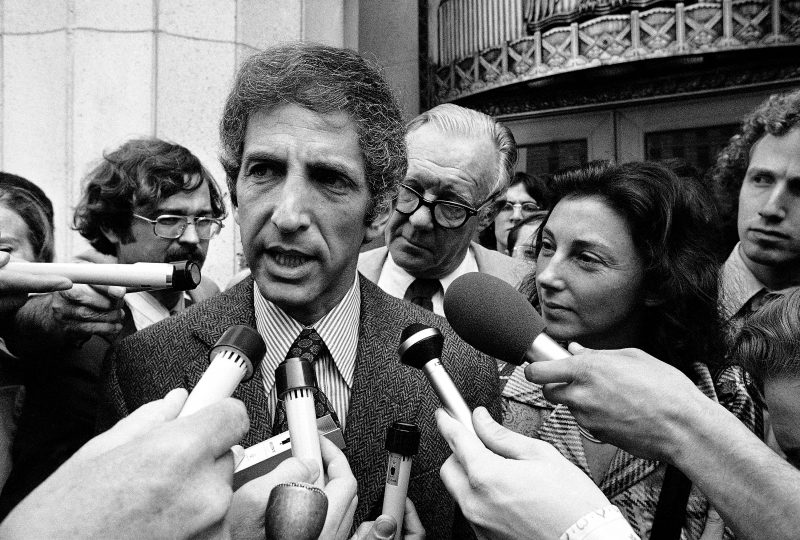

Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the voluminous, top-secret history of the Vietnam War known as the Pentagon Papers, a disclosure that led to a landmark Supreme Court ruling on press freedoms and enraged the Nixon administration — serving as the catalyst for a series of White House-directed burglaries and “dirty tricks” that snowballed into the Watergate scandal — died June 16 at his home in Kensington, Calif. He was 92.

The family confirmed his death in a statement. Mr. Ellsberg announced in an email to friends and supporters on March 1 that he had pancreatic cancer and had declined chemotherapy. Whatever time he had left, he said, would be spent giving talks and interviews about the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the perils of nuclear war and the importance of First Amendment protections.

Mr. Ellsberg, a Harvard-educated Midwesterner with a PhD in economics, was in some respects an unlikely peace activist. He had served in the Marine Corps after college, wanting to prove his mettle, and emerged as a fervent cold warrior while working as an official at the Defense Department, a military analyst at the Rand Corp. and a consultant for the State Department, which dispatched him to Saigon in 1965 to assess counterinsurgency efforts.

Crisscrossing the Vietnamese countryside, where he joined American and South Vietnamese troops on patrol, he became increasingly disillusioned by the war effort, concluding that there was no chance of success.

He went on to embrace a life of advocacy, which extended from his 1971 leak of the Pentagon Papers — a disclosure that led Henry Kissinger, President Richard M. Nixon’s national security adviser, to privately brand him “the most dangerous man in America” — to decades of work advocating for press freedoms and the anti-nuclear movement.

Mr. Ellsberg co-founded the Freedom of the Press Foundation and championed the work of a new generation of digital leakers and whistleblowers, including Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning. He also continued to release secret government documents, including files about nuclear war that he had copied while working on the military’s “mutually assured destruction” strategy during the Cold War, around the same time he leaked the study that made him perhaps the most famous whistleblower in American history.

“When I copied the Pentagon Papers in 1969,” he wrote in the email announcing his cancer diagnosis, “I had every reason to think I would be spending the rest of my life behind bars. It was a fate I would gladly have accepted if it meant hastening the end of the Vietnam War, unlikely as that seemed.”

Commissioned by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in June 1967, the Pentagon Papers comprised 7,000 pages of historical analysis and supporting documents, revealing how the U.S. government had secretly expanded its role in Vietnam across four presidential administrations.

The papers showed that government leaders had concealed doubts about the war’s progress and had misled the public about a troop buildup that eventually took half a million Americans to Vietnam at the peak of U.S. involvement. The conflict cost the lives of more than 58,000 U.S. service members and millions of Vietnamese.

The study was given a bland official title, “Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force,” and a classification of “Top Secret — Sensitive,” an informal designation that suggested the contents could cause embarrassment.

Mr. Ellsberg, one of three dozen analysts who helped prepare the report, had access to a copy at Rand, an Air Force-affiliated research organization in Santa Monica, Calif. As his opposition to the Vietnam War hardened, he began smuggling the papers out of his office, a full briefcase at a time, and photocopied them with help from a colleague, Anthony J. Russo, whose girlfriend owned an advertising agency with a Xerox machine.

Their efforts got off to a rocky start: On their first night copying papers, they accidentally tripped a burglar alarm in the office, drawing the attention of police who stopped by but saw no sign of trouble.

Hoping to hasten the end of the war, Mr. Ellsberg contacted several U.S. senators and tried to share the documents through official channels. When he found no takers, he contacted New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan, leading to the publication of the first story about the files on June 13, 1971, above the fold on the front page of the Times.

The disclosures bolstered criticism of the war, horrified Mr. Ellsberg’s former colleagues in the defense establishment and blindsided the White House. After the third day of stories, the Nixon administration won a temporary injunction that blocked further publication by the Times.

The ruling set up a legal and journalistic showdown, later dramatized in Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-nominated film “The Post” (2017). Mr. Ellsberg, who was played on-screen by Matthew Rhys, had by then started sharing material from the study with almost 20 other media organizations, including The Washington Post, which began printing stories of its own.

When The Post, too, was ordered to stop publishing, it partnered with the Times in court. The newspapers won a landmark decision on June 30, with the Supreme Court ruling 6-3 in favor of allowing publication to continue.

The ruling was hailed as a victory for the First Amendment and an independent press, and seemed to blunt the government’s use of prior restraint as a tool to block the publication of stories it did not want the public to read. It also meant the Pentagon Papers would continue to find an audience even if Mr. Ellsberg, who turned himself in to the authorities, faced a potential 115-year sentence.

He and Russo were charged with theft, conspiracy and violations of the Espionage Act. But a jury never reached a verdict on those charges: U.S. District Judge William Matthew Byrne Jr. declared a mistrial in 1973, citing governmental misconduct so severe as to “offend the sense of justice.”

Among other revelations, Byrne had learned of a White House-directed burglary of Mr. Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office and had seen evidence of illegal wiretapping against Mr. Ellsberg. The judge also reported that in the midst of the trial, he had been offered a job as FBI director by one of Nixon’s top lieutenants, John D. Ehrlichman.

Oval Office tapes revealed that Nixon and his top aides had coordinated to destroy Mr. Ellsberg’s reputation. “He must be stopped at all costs. We’ve got to get him,” Kissinger said during a meeting with the president, shortly after the Supreme Court ruled on the Pentagon Papers. Nixon agreed. “These fellows have all put themselves above the law,” he said, “and, by God, we’re going to go after them.”

The president ordered the creation of a special unit, jokingly nicknamed the Plumbers because of its clandestine efforts to find and fix leaks of classified information. The group broke into the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate complex in Washington, touching off a scandal that culminated with Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

“Nixon’s doom was triggered by Daniel Ellsberg’s massive release of the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and the Washington Post,” Leonard Garment, a Washington lawyer who served as Nixon’s counsel during the scandal, wrote in a 1997 Los Angeles Times essay.

“Nixon and Kissinger,” he added, “let anger overwhelm political judgment.”

Mr. Ellsberg later marveled at what he considered the unintended consequences of the Pentagon Papers. The documents themselves “didn’t shorten the war by a day,” he said, with U.S. bombing in Southeast Asia escalating in the year after their release and American combat troops remaining in Vietnam until 1973.

And yet, he told the New Yorker in 2021, “the criminal actions that the White House took against me … led to this absolutely unforeseeable downfall of a President, which made the war endable.”

“In the end,” he added, “things couldn’t have worked out better.”

Daniel Ellsberg was born in Chicago on April 7, 1931, and grew up in the Detroit suburb of Highland Park, Mich.

His parents, the children of Jewish immigrants from Russia, converted to Christian Science and raised their children in the faith. His father was a structural engineer, and his mother was a homemaker who, beginning when Mr. Ellsberg was 5, pushed him to become a concert pianist. By his account, he practiced six hours a day on weekdays, twice as long on Saturday, and was forbidden to play sports.

When Mr. Ellsberg was 15, his family was in a car crash while driving to visit relatives. His father “apparently fell asleep at the wheel,” according to “Wild Man,” Tom Wells’s 2001 biography of Mr. Ellsberg, and drove into a bridge abutment.

Mr. Ellsberg’s mother and younger sister were killed. His father suffered relatively minor injuries, and Mr. Ellsberg broke his leg, gashed his head and went into a coma. With his mother’s death, he decided not to continue piano lessons.

Mr. Ellsberg enrolled at Harvard on a scholarship and studied economics, graduating in 1952. He spent a year at the University of Cambridge in England, studying on a Woodrow Wilson fellowship, and enlisted in the Marine Corps upon his return. He rose to become a rifle company commander and, after being discharged in 1957 as a first lieutenant, returned to Harvard, receiving a PhD in economics in 1962.

By then he had joined Rand, linking up with like-minded economists who were trying to apply their game-theory research to the Cold War.

Mr. Ellsberg was known as a brilliant theorist, with a paradox in decision theory named for him, but his estranged colleagues later told Wells that he seemed unable to complete his assignments.

In 1964, he was hired as a top aide to an assistant secretary of defense, John T. McNaughton. His first day on the job coincided with the Gulf of Tonkin incident, an apparent confrontation between U.S. destroyers and North Vietnamese patrol boats. Doubts later emerged about official reports, but the incident led Congress to pass a resolution giving President Lyndon B. Johnson broad and open-ended powers to wage war in Southeast Asia.

Mr. Ellsberg’s interest in the war led him to volunteer for his State Department trip to Vietnam, where he served for two years on an interagency task force before resuming work at Rand. He was soon attending antiwar rallies and conferences, including a War Resisters League meeting where he met Randy Kehler, a Harvard student who was headed to jail for his failure to register for the draft.

The experience left Mr. Ellsberg shattered.

“A line kept repeating itself in my head: We are eating our young,” he recalled in “Secrets,” a 2003 memoir. For more than an hour, he sat on the floor of the men’s room, sobbing and thinking about Kehler’s antiwar activism and the sacrifices it entailed. “It was as though an ax had split my head, and my heart broke open. But what had really happened was that my life had split in two.”

Around that same time, Mr. Ellsberg and Russo, one of his friends at Rand, began talking about making the Pentagon Papers public.

As Russo told it, Mr. Ellsberg took some convincing and “rolled his eyes at the ceiling” when it was suggested that he leverage his more influential position to share the contents with the public. He eventually came around to the idea while withholding some of the study’s pages, fearing the Nixon administration might use some of that information to sabotage peace talks.

Mr. Ellsberg’s first marriage, to Carol Cummings, the daughter of a Marine general, had by then ended in divorce. They had two children, who played a small role in copying the papers: Robert, then 13, who tagged along twice and helped with the Xerox machine, and Mary, the younger of the two, to whom her father once handed a pair of scissors and showed her how to snip off the words “top secret.”

In 1970, Mr. Ellsberg married Patricia Marx. They had a son, Michael.

In addition to his wife and three children, survivors include five grandchildren and a great-granddaughter.

Desperate to get the Pentagon Papers into public view, Mr. Ellsberg attempted to have the documents admitted as evidence in a Minnesota draft-board break-in trial. When that didn’t work, he gave them to senators including J. William Fulbright, the Arkansas Democrat and chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee.

Eventually he reached out to Sheehan, an acquaintance from Vietnam to whom he had leaked earlier documents about the war. Mr. Ellsberg gave the reporter a key to his apartment in Cambridge, Mass., where he stashed the files, and insisted that Sheehan could make notes but not photocopy the papers. First, he said, he wanted the Times to fully commit to publishing the materials.

As Sheehan told it, Mr. Ellsberg behaved recklessly during that period. He said Mr. Ellsberg offered to give him the papers but changed his mind, worrying about the risk of imprisonment and the loss of control that came with turning over the documents to a reporter.

“It was just luck that he didn’t get the whistle blown on the whole damn thing,” Sheehan told the Times in 2015, in an interview that wasn’t published until after his death six years later. (Mr. Ellsberg disagreed with that version of events, telling Britain’s Observer newspaper that he “was very anxious for the Times to print it” but was never out of control.)

Sheehan eventually took matters into his own hands. When Mr. Ellsberg was away, the journalist secretly photocopied the papers to obtain them for his editors. Then he prepared for publication while misleading his source, fearing that if Mr. Ellsberg knew what he was doing, he might unintentionally tip off the government.

A few weeks before publication, he again asked Mr. Ellsberg for a copy of the documents, seeking what he described as a kind of “tacit consent” that it was all right to publish. This time, Mr. Ellsberg agreed to share the study, which soon began to appear in print.

Three months after the papers were leaked, members of the Plumbers group, led by E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, broke into the Beverly Hills office of Mr. Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, Lewis Fielding, using a crowbar to pry open a four-drawer file cabinet where they hoped to find information that could discredit Mr. Ellsberg.

That burglary was unsuccessful, as was a May 1972 operation in which a group of Cuban exiles attempted to beat up Mr. Ellsberg while he was addressing an antiwar rally on the steps of the U.S. Capitol.

Barred from government work and unwelcome at Rand, Mr. Ellsberg continued to speak at protests and rallies for the rest of his life. By one count, he was arrested nearly 90 times for participating in protests or acts of civil disobedience.

Much of his activism centered on spotlighting the risks of nuclear war, the subject of his 2017 book “The Doomsday Machine.” Mr. Ellsberg recalled seeing top-secret documents in the 1960s that indicated roughly 600 million people would be killed in a first strike by the United States. The files included a classified 1966 study about the 1958 Taiwan Strait crisis, revealing that American military leaders had called for a first-use nuclear strike on China and drawn up plans for the attack.

Mr. Ellsberg, who quietly posted the study online and first highlighted the document in a 2021 interview, said he hoped to draw attention to the risk of nuclear war at a time of renewed tensions between the United States and China.

He wanted something else, too, telling the Times that he hoped to face federal prosecution so that he could argue against the Justice Department’s increasing use of the Espionage Act. The law had been used to target leakers such as Chelsea Manning, who shared troves of diplomatic cables and battlefield reports with WikiLeaks, and Edward Snowden, who revealed U.S. government surveillance programs.

Mr. Ellsberg said he felt a kinship with those 21st-century leakers, though their methods were vastly different. While Manning and Snowden used digital technology to download and share vast file sets in a matter of minutes, Mr. Ellsberg spent weeks copying the documents with a bulky Xerox machine — “the cutting-edge technology of my day,” as he put it in a 2017 address at Georgetown University.

“Manning and Snowden and I all thought the same words,” he added, “which I heard them say: ‘No one else was going to do it, someone had to do it — so I did it.’”