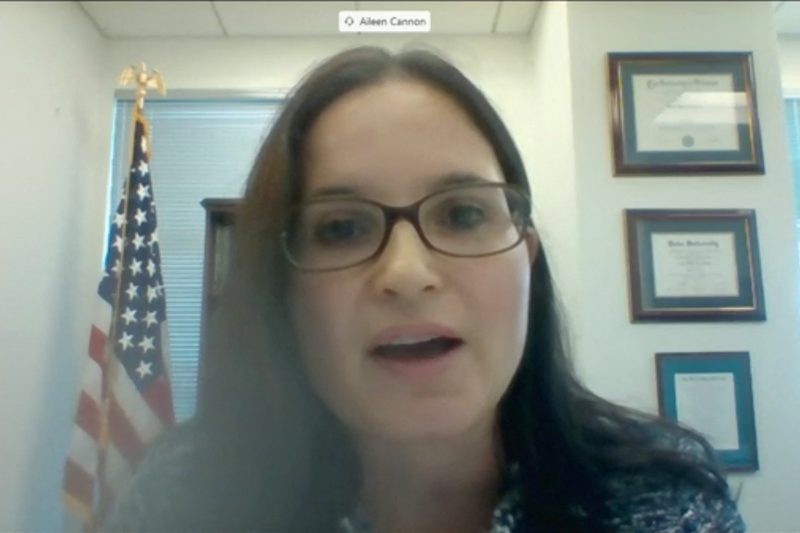

Aileen M. Cannon, the federal judge assigned to the Justice Department’s criminal case against former president Donald Trump, will set the pace and rules for how the unprecedented proceedings unfold.

She will be under intense scrutiny, not least because of her past rulings in Trump’s favor in a case related to the classified documents indictment.

When charges of obstruction of justice and willful mishandling against Trump were unsealed last week, special counsel Jack Smith said he would seek a “speedy trial.” And the Southern District of Florida is known for its “rocket docket,” quickly moving cases to trial.

But Trump, now seeking reelection in 2024, has a track record of dragging out court proceedings, often to his advantage, making Cannon’s role in controlling the timeline even more pivotal.

“She is really in the driver’s seat in terms of the pacing. The danger here is if it backs up into the 2024 campaign or if the case lingers until after Trump is reelected or another Republican elected, and they can direct the Justice Department to drop charges or pardon the president,” said retired federal judge Nancy Gertner, a Harvard Law School professor. “This is a situation where speed equals substance.”

Trump, who has denied wrongdoing, will make his first court appearance in connection with the indictment in Miami on Tuesday before a magistrate judge.

After that, Cannon, 42, who was nominated by Trump during his final year in office and has less than three years experience on the bench, will be in charge.

It is the second time she is overseeing a legal dispute involving the former president. Last fall, Cannon issued a controversial ruling in response to a lawsuit Trump filed that initially slowed the FBI review of classified documents seized at Mar-a-Lago. She was roundly reversed by a conservative panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit.

Her handling of the lawsuit has led to calls for Cannon to step aside as trial judge, a role that court officials say she was assigned randomly after Trump was indicted last week. But legal experts said Monday the Justice Department is unlikely to make a recusal request.

Trump is charged with illegally retaining highly classified documents after he left the White House and of thwarting government efforts to recover the records. The involvement of classified material, as well as the 2024 presidential contest, add significant complexities to the case that could prolong the timeline.

If Trump pleads not guilty and proceeds to trial, as expected, many decisions about whether to slow things down or speed them along will be made by Cannon herself.

“Judge Cannon could delay the case at the request of Trump, either to provide time to adequately prepare for trial or to avoid interfering with his presidential campaign,” said former federal prosecutor Barbara McQuade, a University of Michigan law professor. “She really has the ability to wreak havoc.”

Defendants are entitled by law to a speedy trial, which sets a 70-day time frame. Despite its reputation for efficiency, however, attorneys who practice in the Southern District predicted the case against Trump would proceed more slowly. Based on public statements from Trump and his lawyers, defense attorneys expect the former president’s legal team to file several motions to dismiss the case and limit the evidence that can be presented to a jury.

As the trial judge, Cannon has tremendous power and discretion to resolve pretrial disagreements over access to classified material; claims that Trump is being treated differently than Democrats investigated for possible mishandling of national security secrets; and whether to permit, for instance, the use of key testimony and evidence from Trump lawyer Evan Corcoran.

“The special counsel has thought about all of these things and how to streamline this, but it’s possible for it to get off track,” said Jeffrey Sloman, a former U.S. attorney for the Southern District who was a prosecutor for 20 years.

Cannon is a former federal prosecutor, one of more than 200 mostly young, conservative lawyers Trump nominated to the federal bench. She was born in Colombia, the daughter of a Cuban immigrant mother, and grew up in Miami. She is a graduate of Duke University and joined the conservative Federalist Society while a student at the University of Michigan Law School. She has spent much of her career as a litigator.

Legal experts said Monday that Trump’s role in putting Cannon on the bench is not itself a basis for recusal. But a judge could be asked to step back because of prior rulings. Federal law says a judge “shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

Cannon gained notoriety last September when she intervened in the FBI investigation of Trump’s possession of classified documents after leaving the White House. She appointed an expert, known as a special master, to review the material agents seized last August from Trump’s home and private club, and barred FBI access to some of the materials until the review was complete.

In her order, Cannon suggested that Trump’s position as a former president required special protections, writing that the “stigma associated with the subject seizure is in a league of its own. A future indictment, based to any degree on property that ought to be returned, would result in reputational harm of a decidedly different order of magnitude.”

A unanimous 11th Circuit panel reversed Cannon’s decision, which it said would have resulted in a “radical reordering of our caselaw limiting the federal courts’ involvement in criminal investigations.” The appeals court — whose three judges included two Trump nominees — said it was unwilling to “carve out an unprecedented exception in our law for former presidents.”

Joseph DeMaria, a former federal prosecutor who has practiced in the Southern District for more than three decades, suggested the criminal trial should be reassigned to a judge with more experience, given the complexities of dealing with highly classified material as well as the first federal indictment of a former president.

“She is one of the youngest, least experienced on the federal bench who has never had a case like this,” DeMaria said. “If Judge Cannon was at DOJ, she would not be assigned to this case.”

DeMaria also said it would make sense to reassign the case because of Cannon’s decisions last fall, which he said showed her going out of her way to rule in Trump’s favor. Although Cannon has a reputation as a pro-government judge across a number of other criminal cases, DeMaria noted that she refused in Trump’s earlier case to put her ruling on hold at the government’s request while they appealed.

Gertner, the former judge, agreed that Cannon’s earlier ruling could suggest she is overly sympathetic to Trump and be the basis for recusal. “The appearance of partiality here is not because she ruled in his favor. The appearance issue is the way she ruled in his favor,” Gertner said.

But the decision of whether to step aside is up to Cannon herself. And whether she would do so is a different question. “It is not an easy thing for a judge to do — to admit she has done wrong before,” Gertner said.

Paul Cassell, a former federal judge from Utah, said he is skeptical of calls for recusal just because the appeals court said Cannon erred in her ruling.

“It’s a little unfair to Judge Cannon to say she was doing Trump a solid in some way,” said Cassell, who teaches at the University of Utah law school.

Kendall Coffey, a former South Florida U.S. attorney and Democrat who served on the advisory committee that vetted Cannon for her judgeship, also pushed back on criticism that she would be a “shill” for Trump. “I understand why people would be concerned. But I think she’ll show extreme caution before she does Donald Trump any favors,” Coffey said.

The Justice Department made a conscious choice to bring the case in South Florida, knowing there was the possibility it would be assigned to Cannon. The move — after many months of questioning witnesses before a federal grand jury in D.C. — was designed to prevent Trump’s lawyers from trying to derail the indictment by arguing it had been filed in the wrong place, given that most of the alleged misconduct took place in Florida.

Chief Clerk Angela E. Noble told the New York Times that “normal procedures were followed” in assigning the case to Cannon, one of five active judges who could have been chosen in the assignment system or wheel.

Mark Schnapp, a former federal prosecutor who was chief of the criminal division in the district, said it would be risky for the Justice Department to ask Cannon to recuse.

“You’re asking her to find that she’s partial and can’t conduct a fair trial,” he said. “That’s a lot for a judge to give up.”

Shayna Jacobs and David Ovalle in Miami and Spencer S. Hsu in Washington contributed to this report.