Thirty-five years ago, Americans opened their mailboxes during the HIV-AIDS epidemic to discover a sealed package from the U.S. government. The mass mailing came whether they wanted it or not, and it came with a warning: “some of the issues involved in this brochure may not be things you are used to discussing openly.”

The 1988 mailer, which came from the U.S. Public Health Service, marked a bold step in sex education, launching a public discussion about HIV-AIDS that was grounded in science, and influenced public health efforts on diseases from covid-19 to mpox.

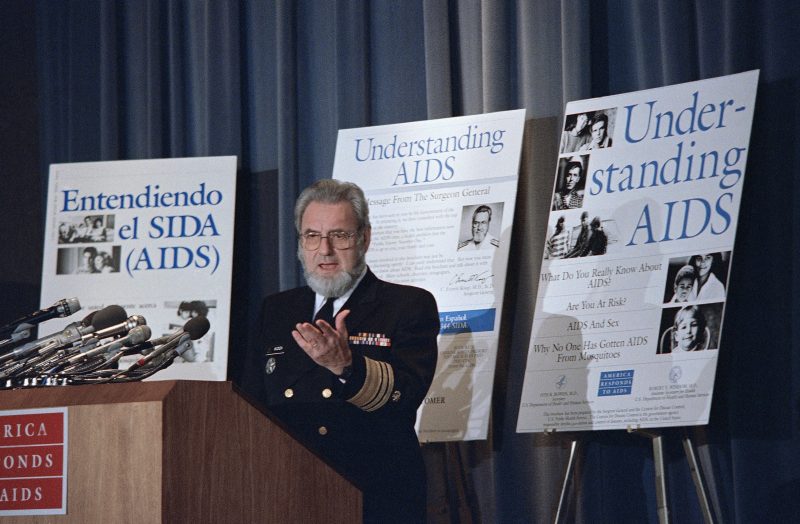

It also caused a firestorm, embroiling the man behind the effort, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop — a charismatic evangelical whom President Ronald Reagan had nominated six years earlier, thinking Koop’s faith meant he would never do anything of the sort.

“He was a guy who surprised everybody,” said Anthony S. Fauci, the retired director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who worked with Koop on AIDS matters.

At the time of the appointment, Reagan and his administration believed they had found the perfect nominee. Koop, a pediatrician, had no background in public health. He was fiercely opposed to abortion and “strongly disapproved of homosexuality,” as he later wrote in his autobiography, “Koop: The Memoirs of America’s Family Doctor.” And he frequently cited the ways his Christian beliefs shaped his medical practice.

His nomination had been incredibly contentious, sparking protests on the left, in the public health community and among organizations such as Planned Parenthood. But his appointment had cemented the Reagan administration’s commitment to the Christian right.

The administration and its allies were confident that Koop would be an evangelical Christian first and a public health advocate second. Much to the administration’s shock, the opposite turned out to be true.

During his tenure, Koop used his position as a bully pulpit. Making “a special point of wearing my uniform,” he wrote, he appeared on talk shows, at high schools and at churches to share his views on everything from smoking to nutrition. As Time magazine put it, “Surgeon General C. Everett Koop has an opinion, which he will give you with great certainty at high speed.”

He did not, however, share his views on the emergence of a new disease: HIV-AIDS.

While Koop disapproved of homosexual acts, he believed, as a physician and a Christian, that his work entailed protecting the public’s health. And he came to believe, too, that conservatives in the “Reagan administration attempted to thwart my attempts to educate the public about AIDS,” he wrote.

In 1986, Koop reached a breaking point. He turned to one of the primary tools at his disposal: the creation of a new surgeon’s general report. Beginning in 1964, when Surgeon General Luther Terry had released a groundbreaking report on the dangers of smoking, these reports had highlighted public health concerns.

Now Koop, with the assistance of a few public health officials, wrote a detailed and explicit report about HIV and how Americans could and should protect themselves.

The federal government had been creating sex-education materials since 1918, pamphlets that typically had taken one of two approaches. Those intended for the general public relied heavily on euphemisms and vague language. Those intended for the military used slang terms, warning to avoid “whores” for fear of contracting “the clap.”

By contrast, Koop used specific and highly clinical terms in his report, referencing “oral, anal, and vaginal intercourse.” He believed neutral language would prevent readers from allowing their moral or religious beliefs to cloud their judgment of a medical issue.

“You cannot get AIDS from casual social contact … such as shaking hands, hugging, social kissing, crying, coughing or sneezing,” the report stated. It also cannot be transmitted via “toilets, doorknobs, telephones, office machinery, or household furniture.” But the report went even further, explaining that “you cannot get AIDS from body massages, masturbation, or any nonsexual contact.”

Reagan administration officials were incensed by the explicit language. William Bennett, the secretary of education, seethed that the report’s emphasis on the use of condoms might be “clinically correct [but] it was morally bankrupt.”

Hoping to head off Koop and prevent the release of information about condoms to an even wider audience, Reagan’s Health and Human Services officials created their own campaign in 1988. Using the slogan “America Responds to AIDS,” the new campaign provided no real guidance about how Americans could protect themselves against this new disease. It did, however, promote abstinence.

Frustrated by the administration’s approach, legislators in Congress turned to Koop. They asked for information about AIDS to be distributed directly to every American, regardless of where they lived or who they were, and appropriated $20 million for the effort — to be cleared by health leaders, not the White House. The seven-page “Understanding AIDS” mailer, a highly condensed version of Koop’s 1986 report, was the result, made available in English and Spanish..

The logistics in preparing the mailer were laborious. Just printing it took 20,900 miles of paper. The Public Health Service requisitioned railroad cars to store the 114 million copies of the mailer before its release.

“Understanding AIDS” spoke to recipients unwaveringly. It stated that “condoms have been shown to help prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases” and recommended their use. “The White House doesn’t like the C word,” Koop told a Time reporter. “But if you don’t talk about condoms, people are going to die.”

In the wake of its arrival in American mailboxes, political and religious leaders on the right took to the airwaves to denounce it.

The evangelical preacher Jerry Falwell said Koop should have simply said “no sex outside of marriage …[and] saved taxpayers’ money.” Judie Brown, the head of the American Life League, a Catholic organization that opposed abortion and contraception, said “disinformation abounds” in the brochure. The report, she alleged, “caters to such lifestyles as homosexuality and bisexuality by avoiding even a modest encouragement toward a type of sexual relationship designed by nature for man and woman to become one in marriage.”

Cartoonists had a field day, depicting parents warning children against opening anything from the surgeon general. Boston Globe cartoonist Dan Wasserman drew Reagan lamenting to an aide the release of Koop’s “filthy little book.” Reagan himself did not speak publicly about the mailer.

The media storm, ironically ensured that the pamphlet became a major news story. Follow-up surveys indicated that more than 80 percent of Americans read the mailer. Call centers that had been set up to answer questions were overwhelmed by callers eager to learn more.

“Understanding AIDS” would mostly be forgotten in the years that followed. But it marked a turning point in AIDS education — and in public health.

“You saw a surgeon general,” Koop’s successor Richard Carmona said in 2009, “change the way our nation and the world dealt with an infectious disease.”