Record efforts to ban books are fueling fights in Texas, Virginia and across the country. Just this week, a group including free-speech advocates, authors, parents and the publisher Penguin Random House filed a federal lawsuit against a Florida school district over the removal of books covering gender and LGBTQ issues.

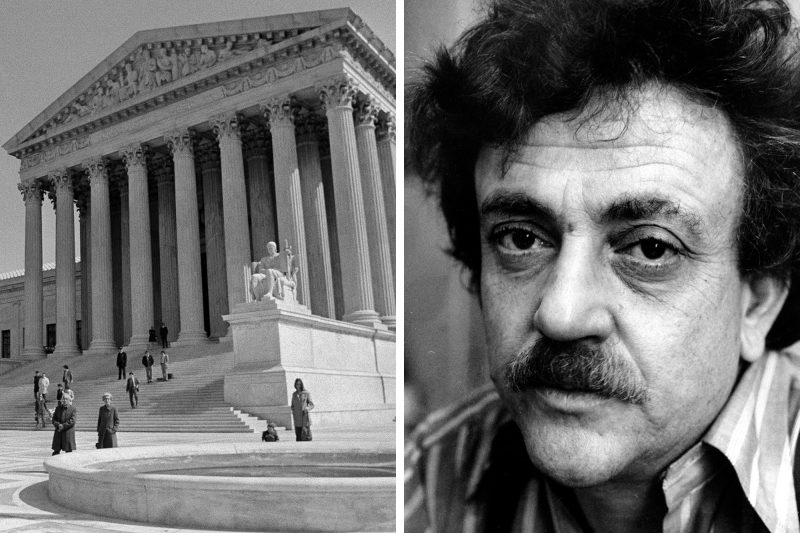

Yet only one previous case of a library book ban has ended up before the Supreme Court: Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico. And, outside law school classrooms, it has largely been forgotten.

The country was engulfed then, as now, in a debate over which books should be allowed in schools and libraries. The American Library Association recorded a rise in censorship activity, from 100 book removals or challenges annually in the early 1970s to 1,000 annually by the end of the decade. In Virginia, a pastor fought a public library for offering books such as Philip Roth’s “Goodbye, Columbus” and Sidney Sheldon’s “Bloodline,” calling them “pornography.” In Indiana, a group of senior citizens publicly burned 40 copies of a book called “Values Clarification” for its discussions of moral relativism, situational ethics and secular humanism. (It also mentioned marijuana and divorce.)

The Pico saga began in Levittown, a hamlet on Long Island, in September 1975, when three members of the Island Trees school board attended a conference sponsored by a conservative education group, Parents of New York United. At the conference, PONY-U shared a collection of excerpts from books it deemed “objectionable.”

The president and vice president of the board thereafter searched the library of Island Trees High School. They discovered nine of the listed books, including Richard Wright’s “Black Boy” and Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five.” Another was found in the junior high library.

A few months later, the board formed a book review committee, which recommended removing two of the books and making a third available only with parental approval. The full board rejected these recommendations, instead withdrawing all nine books for being “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Sem[i]tic and just plain filthy.”

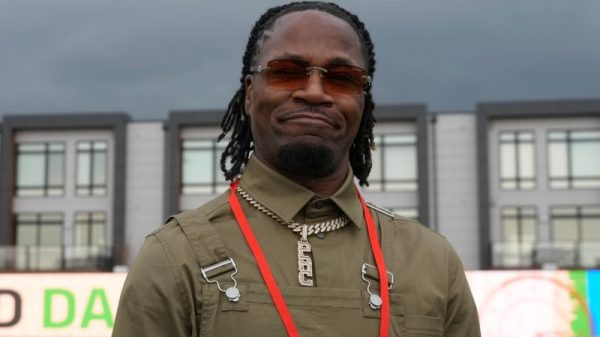

The New York Civil Liberties Union, on behalf of Island Trees student council president Steven Pico and four other students, sued the board in response on Jan. 4, 1977. Ira Glasser, the organization’s executive director, said at a news conference that the ban had been part of a recent “epidemic of book censorship” by “self-appointed vigilantes.” Vonnegut, who was also in attendance, chain-smoking, said he was “distressed that this sort of thing can happen in my country.”

Long Island in the 1970s, recalled Russell Rieger, a New York-based tech executive and one of the original plaintiffs, was highly conservative. Many of his friends and neighbors “were as Archie Bunker as you can imagine,” Rieger recalled. Most of the banished books, similar to ongoing book-banning efforts today, dealt with race and with racial and ethnic minorities: “Black Boy,” Eldridge Cleaver’s “Soul on Ice,” Piri Thomas’s “Down These Mean Streets,” Oliver La Farge’s “Laughing Boy” and “Best Short Stories of Negro Writers,” edited by Langston Hughes. The board also nixed the anonymously published “Go Ask Alice,” about a drug-addicted teen girl, and Desmond Morris’s “The Naked Ape,” a zoological approach to human evolution.

The students asked a New York federal court to declare the board’s actions unconstitutional and order the board to return the nine books, which they claimed had been banned not because they lacked educational value but because “particular passages in the books offended [the board members’] social, political and moral tastes.”

“Most people believed the board was right and we were radicals,” Rieger said, a perspective that didn’t bother him. “It was a badge of honor,” he said.

After an initial burst of media attention, the plaintiffs returned to being students, leaving the legal work to the lawyers. In 1979, the district court ruled in favor of the school board. It reasoned that while “removal of such books from a school library may, indeed in this court’s view does, reflect a misguided educational philosophy, it does not constitute a sharp and direct infringement of any first amendment right.” An appellate court reversed that decision in 1980 and remanded the case back to district court, prompting the Supreme Court to step in.

In June 1982, the court ruled 5-4 in the students’ favor. In his opinion, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote that while “local school boards have a substantial legitimate role to play in the determination of school library content,” those boards’ authority “must be exercised in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.” In other words, school officials can’t ditch books just because they don’t like them.

Yet the case wasn’t the constitutional slam dunk its supporters had hoped. Only two justices fully joined Brennan’s opinion, while two others agreed with parts of it. One, Justice Harry A. Blackmun, concurred that the Island Trees board should not have removed the books but rejected Brennan’s argument that the students had a First Amendment right to receive information.

Although such plurality decisions are binding, they set a weak precedent. Indeed, in a case decided just three months later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit remarked that Pico was “of no precedential value as to the application of the First Amendment.”

Genevieve Lakier, a law professor at the University of Chicago, said the Supreme Court was trying to balance two competing considerations: that students should be exposed to all sorts of ideas in their quest to learn, and that local school boards have a mandate to regulate that exposure as they see fit.

“The line that the court draws is a very fine one,” Lakier said — too fine to settle the matter for good.

The court’s decision didn’t immediately calm any turbulence in Levittown, either. Over the summer of 1982, 1,200 Island Trees parents petitioned to return the banned books to the library shelves. The board wanted to slap the books with a “Parental Notification Required” warning, but New York Attorney General Robert Abrams said that move would violate a state law on the confidentiality of library records. Finally, in early 1983, the board restored the books with no restrictions, though it did so reluctantly. “Until the day I die,” board member Christina Fasulo said in a New York Times interview, “I refuse to budge on my position. Since when is it demeaning to take filth off library shelves?”

That debate goes on. Could it land at the Supreme Court a second time?

“I would love for the ACLU to pick it up,” Rieger said. “But I would be nervous about it happening now.”