President Biden’s State of the Union address aimed to appeal to as many Americans as possible. That’s neither a revelatory comment nor a surprising one; he’s a politician trying to build political support — and building political support is about presenting voters with appealing policy proposals. (Also furious tirades in the partisan media, of course, but that’s less Biden’s style than that of some in the audience Tuesday night.)

So the president delineated a slew of average-Jane ideas: increasing employment, limiting random fees from companies, making insulin affordable, that sort of thing.

“Too many of you lay in bed at night like my dad did, staring at the ceiling and wondering what in God’s name happens if your spouse gets cancer, or your child gets deadly ill or something happens to you,” Biden said. “What are you going to — are you going to have the money to pay for those medical bills? Or are you going to have to sell the house or try to get a second mortgage on it?”

As he outlined these policies aimed at bolstering the working class, Biden wrapped them in a very pointed envelope. There should be more, better jobs — but there should also be more union jobs. Because Biden, long an ally of the labor movement, understands acutely the difference between support from working Americans and organized support from them.

The first guest Biden introduced during his speech was a woman named Saria Gwin-Maye. Biden was boasting about the passage of legislation aimed at improving American infrastructure, and Gwin-Maye was hailed as one of the laborers who would be working to replace a notoriously decrepit bridge over the Ohio River. But Gwin-Maye isn’t just a worker. She’s a union member, a member of Ironworkers Local 44.

Similarly, Biden didn’t just argue that the country should “make sure working parents can afford to raise a family with sick days, paid family medical leave, affordable child care.” He did so immediately after touting the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, legislation that would make it easier for workers to form unions.

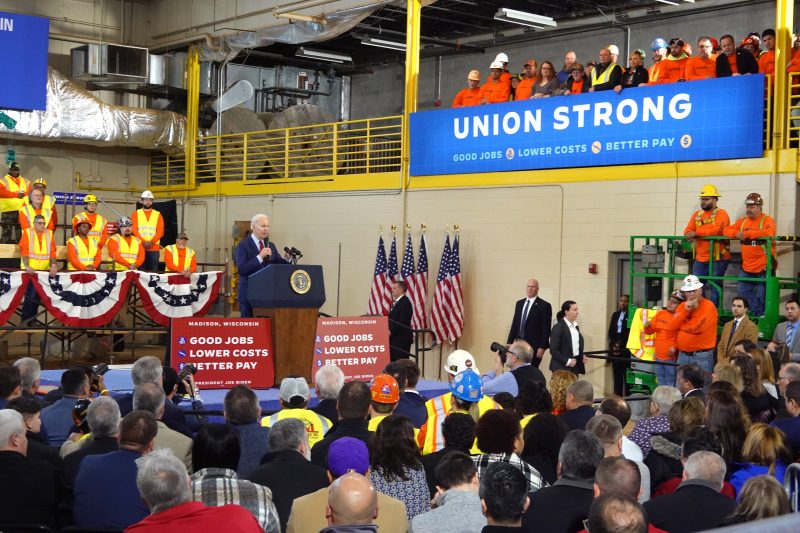

He left Washington on Wednesday to continue advocating for his administration’s efforts on the economy. He traveled to Wisconsin, where he spoke before members of the Laborers’ International Union. A banner on the wall read, “Union Strong.”

The reason this matters is not a secret. Political parties exist in large part as storehouses of power; even if Biden goes away, the party collectively still has power through its other elected officials and its registered members. The party endures even as candidates and voters come and go. The power of the party, meanwhile, is such that it allows for the election of individuals as president — something that is all-but-unattainable outside of the party.

Labor unions exist for a similar reason: There is an aggregated power that isn’t dependent on individual workers or even individual workplaces. The weight of the union can be brought to bear in organizing fights, and the weight of the labor movement broadly can be brought to bear on employers — or politicians.

Traditionally, labor unions have supported Democratic candidates. That’s largely because Republicans have typically been the party of business owners, the natural foes of unions. But this relationship has been strained over time. Union members often haven’t attended college, and college attendance is increasingly correlated with support for Democratic candidates. So, over time, the partisan gap among members of union households has narrowed.

Some Republicans, like Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), see an opportunity here: Supporting union members who agree with the GOP on cultural issues might help bolster the party’s base. The party’s increasing hostility to businesses that advocate for issues like diversity meant that, when Amazon employees wanted to organize, Rubio sided with the workers and not the corporation. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

Unions still retain the ability to influence their members in a number of ways. The labor movement is also effective at turning out its members, a group that still skews Democratic. So for Biden and his party, it’s useful to bolster unions because that institutional strength is still beneficial. Put another way: Unions can probably do a better job of convincing their members to vote for Biden than Biden can.

But union membership continues to slip. There was a blip of an increase during the pandemic, when union workers were better protected against massive layoffs. But in 2022, the percentage of workers who belonged to unions or who were represented by unions was the lowest on record.

This is the flip side of Biden’s focus on unions: By working hard to strengthen them, he aids his party, but he also aids the unions, increasing loyalty to Democratic candidates.

This is a long-standing alliance. Which is probably why Biden focuses so heavily on unions. There are few politicians in America more old-school than Joe Biden, and there are few Democratic priorities more old-school than bolstering the party’s relationship with labor.