From the earliest months of the coronavirus pandemic, there was a partisan divide in the nation’s approach. Then-president Donald Trump fostered this, certainly; his eagerness to get the country back to some semblance of normal with his reelection approaching was unsubtle. But his audience was receptive. Ingrained Republican skepticism of authority was parlayed into skepticism about recommended approaches to containing the virus: distancing, masking and, eventually, vaccination.

One result was that polling repeatedly showed Republicans as less likely to express concern about the virus or to take steps to prevent infection. After vaccines became widely available, Republican-voting counties were more likely to see covid-19 deaths relative to their populations than Democratic-voting ones. In fact, research has shown an explicit gap in the death toll between Republicans and Democrats.

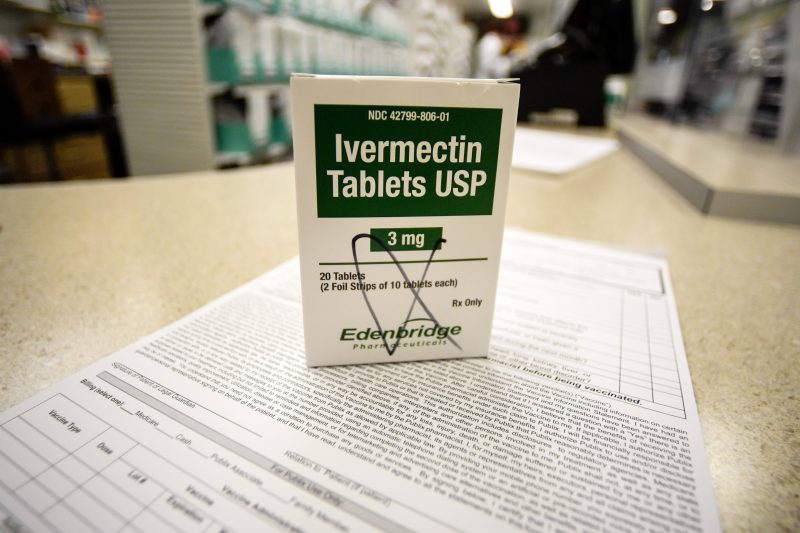

Not only were Republicans more likely to reject recommended approaches to the virus, they were more likely to embrace unproved ones. Trump’s effort to hype hydroxychloroquine as a solution to the virus — and thereby to tout his “expertise” against government doctors — was echoed among others on the right despite a lack of evidence that it worked. Later, the anti-parasite medication ivermectin was hailed as an effective treatment. That too lacks credible evidence, but it became an article of faith among Trump supporters that there were cheap, effective medicines that drug companies were trying to hide. Research showed that counties Trump won in 2020 were more likely to see prescriptions for ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.

Research being published next week helps explain that latter finding. It turns out that doctors who are politically conservative were actually more likely to consider hydroxychloroquine as an effective treatment, despite the understood research.

That determination comes from a forthcoming paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by a team of researchers from the University of Pittsburgh. From April 2020 to April 2022, the researchers surveyed a group of doctors and a group of laypeople at the same time.

“In each survey, physicians evaluated a clinical vignette about a severely ill COVID-19 patient and made decisions about which treatments to administer,” the report on the research explains. “For each treatment option, physicians reported beliefs about effectiveness and the quality of clinical evidence and made incentivized predictions about the proportion of their peers who made the same decision.”

The result?

“[C]onservative physicians were approximately five times more likely than their liberal and moderate colleagues to say that they would treat a hypothetical COVID-19 patient with hydroxychloroquine,” the researchers write. “ … This difference was driven in large part by agreement between liberal and moderate physicians, with conservative physicians displaying polarization that was often comparable to that of conservative laypeople.”

You can see that on the chart below. The pink line (opinions of doctors) and the green lines (of laypeople) are presented relative to how political moderates view the effectiveness of each treatment. The higher the line goes, the more effective the treatment is believed to be.

In each case, the pink/doctor line is generally flat from left to center, showing that liberal and moderate doctors were in agreement on the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin and vaccination as treatments. And, in each case, the pink line tracks with the layperson perspective as it extends to the right, with conservative-leaning doctors generally viewing ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine as more effective than more moderate ones.

The research included asking participants to evaluate scientific research on the drugs.

“[P]olitical ideology colors the evaluation of scientific evidence to a greater degree when it pertains to a politicized treatment,” the report reads. “After reading otherwise identical results, partisans’ responses were more polarized when the drug was identified as ivermectin relative to when it was anonymized, with participants who were more conservative reporting that the evidence was less informative, the study was less methodologically rigorous, and the authors were more likely to be biased.” The results, they add, “were not detectably different across lay and physician samples.”

In other words, partisans were more likely to dismiss research undercutting the efficacy of ivermectin when they knew the research was about ivermectin.

This is a fascinating finding, if not an entirely unexpected one. It is also a finding that casts the disparagement of “follow the science” as a guideline encouraging acceptance of formal recommendations in a new light. Given that “the science” was viewed through a partisan lens, it’s not surprising that research bolstering the consensus was dismissed on the right and research purportedly undercutting it embraced.

You perhaps noticed on the third graph above that conservative doctors were about as likely as conservatives overall to view vaccination as less effective than moderates. This, too, comports with the national partisan trend — with tragic results.

The headline of this article originally stated that ideology was meaningfully associated with doctors’ willingness to prescribe ivermectin. It was instead associated only with hydroxychloroquine and vaccination.